Hi m’dears!

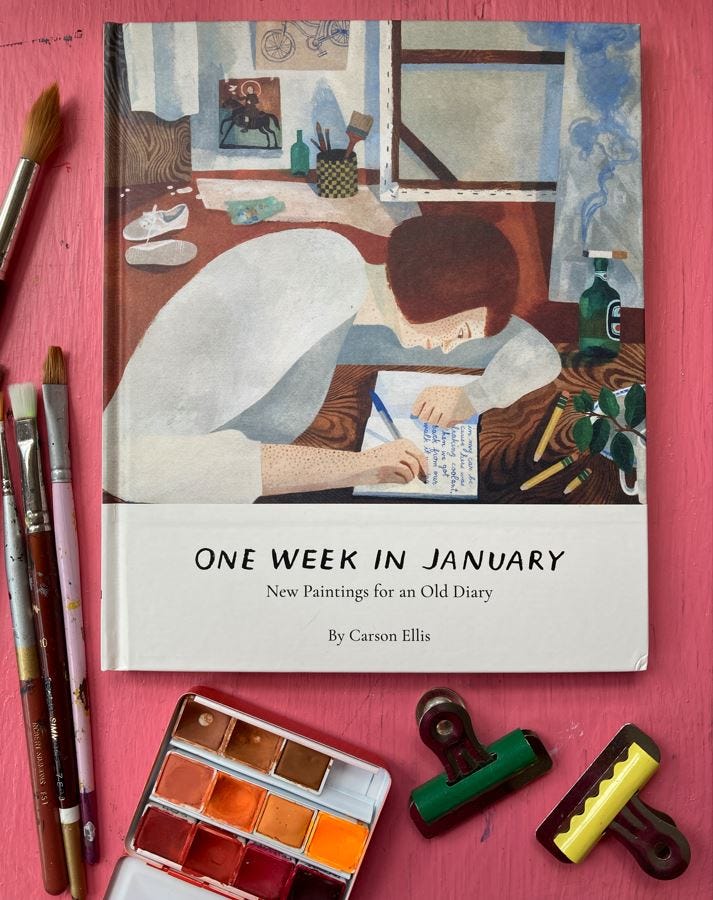

Back last fall, one of the great joys of the first part of my freelance career was working with author and artist Carson Ellis on her first book for grown-ups, One Week in January: New Paintings for an Old Diary. I acquired this strange and wonderful book while I was still an editor at Chronicle Books, and getting to continue working on it with Carson after my departure was such a privilege. For this book, Carson created a series of beautiful new paintings to illustrate a meticulously detailed diary she kept for one week in January 2001. Recently, Carson and I reconnected to discuss the project. So, today’s newsletter is a bit of a departure from our usual fare. A bit like an interview, a bit like a conversation. Packed with interesting insights about art-making, memory, minutia, nostalgia, the analog, the passage of time — not to mention positively gorgeous artwork (and a few surprise visuals as well). And, never fear, there’s still a mix tape for you at the bottom, too. Read on!

Bridget Watson Payne: Ok! So, what would you say was the starting point for this project?

Carson Ellis: I think there were two convergent starting points. The first one was when you initially reached out many years ago to suggest we work on a book together - one for adults. From that point on I followed what you were doing as an editor and also as an artist and I liked it. At one point I pitched an illustrated edition of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood to you, which is funny because in One Week in January I’m reading that book for the first time. I loved it then, and in the journal I kept in 2001 Colin suggests I illustrate it. Ten years later I pitched the idea to you (then dropped the ball on it). And ten years after that we worked together to publish the journal I kept the week I first read it. There are so many long threads running through OWIJ.

Anyway, the second starting point was when I unearthed this journal in late 2020. It was at the bottom of a milk crate - 8 1/2 single spaced pages. I hadn’t seen it in decades and I just liked it. I thought it was funny and I also thought it was moving to read about my broke, twenty-five year old pre-digital life. I couldn’t tell if it would be funny or poignant to anyone but Colin and me, so I wrote to you about it with a million caveats: maybe it should just be zine; you won’t hurt my feelings if you don’t like it, etc.

BWP: Yep, I definitely felt like I was stalking you a little bit for many years there. Back when I was an editor for Chronicle Books. In the nicest, gentlest possible way, of course! Like, I wonder if Carson wants to do an adult book now? Five years pass. Maybe now? Another five years pass. Maybe now?

And then, in the middle of the pandemic, you sent me the diary, with all those caveats, and I just immediately loved it so much. I mean, it is very much my personal taste. I love mundane things, boring things, everyday life. And we're close to the same age so the nostalgia factor was strong for me, too. But I felt pretty sure other people would like it, too, not just me. Especially given that your idea was to illustrate it. How did you come up with that concept?

CE: I was so unsure of it, and the fact that you loved it made it happen and gave it life. I think if you had hesitated I would have been like, “Yeah, no. This was a silly idea. I’ll just make it into a zine." And then I would have never even made it into a zine. I’m so glad I sent it to you. I’m not sure anyone else would have seen its potential as you did. And now that it’s a book, I love it. I’m so proud of it. So, thanks.

Conceptually, I knew I would illustrate it. I don’t think I’m interested in making a book without art. The text is so spare and dispassionate and as a diarist I reveal so little emotionally. I liked the idea that the art would reveal more than the words - that there would be a dissonant relationship between the two.

BWP: Right – and that dissonance is temporal, too, since the text and the art are created decades apart. I can't think of another book like that, where the same author created both the words and the pictures but at such different times in their life. The dispassionate words of youth combined with the much more emotional artwork of middle age. God, I just love that whole concept so much!

But I remember in the early days of working on it, you weren't sure what art style or medium you wanted to use. And you do make work in a number of different ways. How did you end up settling upon making the kind of art we ended up with?

CE: Yeah, initially my vision for the art was more eclectic. It seemed like a cool opportunity to use a mix of mediums - pen and ink, pencil drawings, paintings - whatever struck my fancy. I wanted really fleshed out full bleed paintings but also loose, fast paintings with lots of negative space. Sort of like a scrapbook. I'm always illustrating books for kids, and to me that means choosing a medium and an approach and sticking with it until the book is done so it feels cohesive. That sometimes feels like a creative burden so I was going to take this moment to do the opposite.

But once I started working I found I only really wanted to make the laborious paintings. Early on you and I looked at a collection of tentative work that I had made for this book. The strongest pieces were the paintings and I think the direction was clear. And in the end I think it served the book to have a cohesive body of work. I think it helped the two voices – the voice of the 25 year old writer and the 48 year old painter – be distinct. But we did end up putting a few pen and ink drawings in the front and back matter. They illustrate fictional characters in the book: a trumpet player in a Decemberists song, some Victorian wrestlers I was looking for pictures of online, the characters in the book that Colin and I were writing back then.

Does One Week in January look like you thought it would when we first started talking about it three years ago? You were such a supportive editor – so hands-on, yet I also felt very free to make the book I wanted to make.

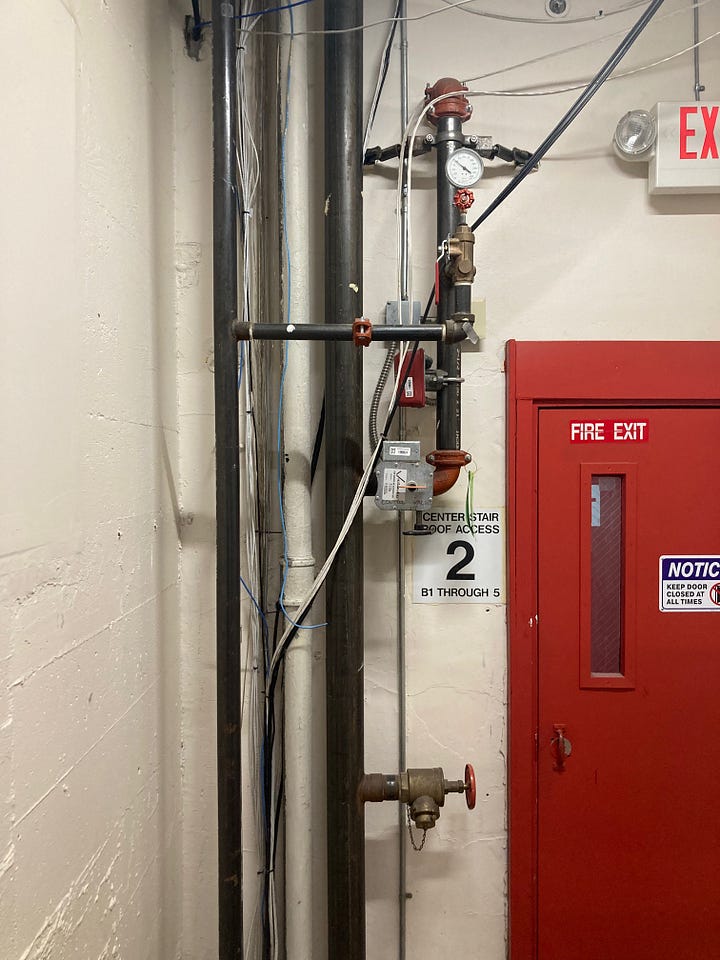

BWP: Ooh, good question. I would say it both does and doesn't. It's like everything I ever dreamed of and yet somehow even better. I've always been drawn to your most lush, painterly work, so it's exciting to me that the art went in the direction it did. And some images, like climbing up on the roof toward the end of the book, are almost exactly how I imagined them from the start. But overall I think there's more artwork – for sure more portraits, and I think also more detailed scene-setting stuff, like the stairwell image on page 38 – than I expected. Didn't you go and do some actual location scouting back in your old neighborhood for some of those paintings?

CE: I did, yes. I went back to the warehouse I used to live in. I brought my younger kid, Milo, who was nine at the time. We snuck in the front door while a guy with a cart of produce was on his way out. Milo was not into this – sneaking into the warehouse or hanging out in there with me while I took photos. He thought it was a creepy place. Back when I lived there, I was constantly running up and down the stairs in that stairwell. Colin and our friend Stiv lived downstairs where the phone, computer, and kitchen were and I was always dashing between my place and theirs. I hadn’t set foot in that stairwell in 20 years but the echoey sound in there was still so resonant. It brought so much back. I would’ve stayed in there for a long time if my poor kid hadn’t been begging me to leave.

Another time I drove into Portland from the suburbs where I live and walked around my old neighborhood - I think you’d call it the inner southeast industrial district. It’s mostly warehouses around there. I used the photos I took that day to paint a lot of the exterior scenes in the book.

And then, another time, I had Colin drop me in that neighborhood after a date night. We had a nice dinner and I was a little drunk and he dropped me at our old warehouse so I could take a reference photo for the last painting in the book - the one with the red candle. I ran around in the rain taking pictures and then took a Lyft home. In retrospect I don’t know why I didn’t have Colin wait for me while I took those photos. Maybe I wanted to have a solo nighttime adventure like I might have had in 2001.

BWP: Oh man, I love the story of you running around on your own after your date – for no terribly good reason! It feels so in keeping with the spirit of the book. Did you find yourself having a lot of emotions or thoughts as you worked on the book – about the past or the passage of time – or other things? Was it a positive experience? A nostalgic one?

CE: Initially it was overwhelming. I spent a lot of time looking at old pictures and listening to the music that meant the most to me back then. I immersed myself in my life at twenty-five, and it made me sad. In the beginning I cried a lot, especially listening to music; Neutral Milk Hotel and Cat Power just wrecked me. I didn’t expect that.

2001 was actually a pretty grim year for me. Not only because I was broke, but also because a bunch of people in my social scene died around that time, too young, in tragic ways. I was in an on-again off-again relationship with Colin that was breaking my heart. I went back to work in a bar and that scene could be dark. My prospects as an artist were scant. So yes, I was nostalgic for a carefree time before kids and iPhones. But it was also a hard time that I wouldn’t want to relive. I think the crying was as much about all the feelings that I didn’t let myself feel in 2001 as it was about missing that life.

Eventually though, the shock of finding myself back in that world wore off, and then it became a really positive experience. I reached out to lots of old friends. Memories came flooding back, both good and bad. It was cathartic to make this book; a really beautiful experience.

BWP: That makes sense. It's kind of funny because, even though the diary itself is so dry ("I decided to have cereal instead though, and to save my bagel for lunch") it's somehow still so moving, so evocative of a certain time, and place, and all of these relationships (which is one of the big reasons I was so drawn to it, and thought readers would love it, too). Add to that the personal experience for you -- of looking at your photos, listening to the music you listened to back then (the music of your youth is always going to be an emotional gut punch, right?). And, yeah, I'd actually be kind of amazed if you hadn't cried a bunch.

Do you think there's anything else to be said about the differences between the two eras? Either in your own life -- your 20s versus your 40s and how you feel about those two times of life and the space between them -- or else the 1990s versus the 2020s and how the world has changed? The analog of it all...?

CE: I feel like everything has changed between then and now. In 2001 the internet was a novelty. I didn’t have a cellphone, let alone an iPhone. I didn’t text. I called my friends and wrote them long, long emails. If I wanted to watch a movie, I went to the video store or maybe I got a DVD in the mail from Netflix. If I wanted to listen to music, I bought a CD.

That year, everything was beginning to change in a radical, irreversible way. I was and still am averse to tech. I was a late adopter of cellphones and I didn’t want a computer. But I could not withstand the tidal wave of technical advancement that was coming for us all. What strikes me when I read this journal is not so much what has changed since then. It’s that I didn’t really know it was happening. I didn’t understand the magnitude of the change. I didn’t know that the digital age was upon me and I would never be able to go back. This is another thing I think I may have been crying about while I worked on the book. I long for a time before iPhones and social media.

BWP: I know what you mean. Looking back on that time (especially if you're a slow-tech-adopter / tech-reluctant type person, like you and I both are – but I think even for people who are not that, to some degree): we were in the process of losing something, without knowing we were losing it. There was no way for anyone to know what we were losing because there was no way to know what was coming next. So now, looking back – like with any loss – there's a kind of grief. Not necessarily because one is so nostalgic for CDs or video stores or long emails or phone calls per se (though it can certainly feel that way sometimes) – but because of the forms of life that those things represented. Embodiedness, tactility, in-person community. Which aren't gone, but can feel harder to access.

This all makes me think -- do you feel like the book has something to say (either in the subtext of the project itself, or else just in your own experience as you worked on it) about aging?

CE: Good question. I’m sure it does, but I’m not sure what that is yet. Maybe I have to wait another twenty-five years for some lesson to reveal itself. I bet the seventy-five year old woman reading the book that she wrote when she was twenty-five and illustrated when she was pushing fifty will have some thoughts about aging.

BWP: Oh amazing! I wonder if there's some other form of creative expression that 75-year old you will make about the project to add to it? Lie, the 25-year old writes, the nearly-50-year-old illustrates, and the 75-year old sings a song or plants a garden or knits a sweater that's somehow about these same experiences. That would be amazing.

CE: The seventy-five year old programs her AI assistant to recreate her 2001 warehouse as a virtual reality space where you can smoke cigarettes and try to assemble a futon.

BWP: Oh god. I'm dying.

Ok, anything else you want to talk about? Any other big picture themes? Little nitty-gritty stuff?

CE: I don’t think so. I would just say that it was an absolute pleasure working with you, Bridget. I hope we get to do it again.

BWP: YES. I was so so happy that I got to keep working on this book! When I departed Chronicle not super long after having acquired it, I would have been so sad to not have continued to be your editor. So the fact that things played out in such a way that I got to go on working with you as a freelancer was just so wonderful. We had so much fun! And, I mean, of course it was a lot of hard work. But it was such a rewarding creative process. I feel really proud and lucky to have been a part of it.

And I'm really looking forward to your show at Nationale!

CE: Thanks! Me too! See you in September.

Mix Tape

By 2001 we were making mix CDs, not tapes, but the spirit remained the same.

This one here? It’s a banger. Just saying.

xo

b

Your interview was wonderful, I'm in love with this book. Can't wait to get it. Thanks!